Cristián Simonetti is Associate Professor in Anthropology at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. His work has concentrated on how bodily gestures and environmental forces relate to notions of time in science. More recently he has engaged in collaborations across the sciences, arts, and humanities to explore the environmental properties of materials relevant to the Anthropocene. He is the author of Sentient Conceptualizations. Feeling for Time in the Sciences of the Past (2018), co-editor of Surfaces. Transformations of Body, Materials and Earth (2020) and co-editor of a forthcoming special issue of the journal Theory, Culture & Society entitled “Solid Fluids. New Approaches to Materials and Meaning.”

Figure 1: Obsidian arrowhead found in central Chile. Courtesy Aksa Cancino

Indigenous peoples of South America crafted obsidian tools, relying on extensive trade networks that reached as far as the southern tip of the continent — the last region to be occupied by humans (Stern, 2018; Méndez et al 2018). These indigenous hunter-gatherers carried with them a longstanding tradition that dates back to some of the earliest hominins of the Lower Palaeolithic, also known as the Early Stone Age. Obsidian has been present throughout nearly the entirety of human prehistory, likely serving as a preferred material for toolmaking due to its uniquely brittle composition, which allows for the creation of exceptionally sharp edges through knapping.

Some of the earliest known obsidian tools have been uncovered in Ethiopia’s highlands by archaeologists at the Melka Kunture site and are dated to approximately two million years ago. These tools, attributed to the Oldowan and early Acheulean lithic industries, were crafted by early hominins, as confirmed by fragments of a mandible from an infant *Homo erectus* found in stratigraphic association with the tools (Margherita et al. 2023). Since those early beginnings, the skill of crafting obsidian tools was carried forward by successive hominin species, including *Homo sapiens*, and eventually reached South America, some 7,000 years before the present.

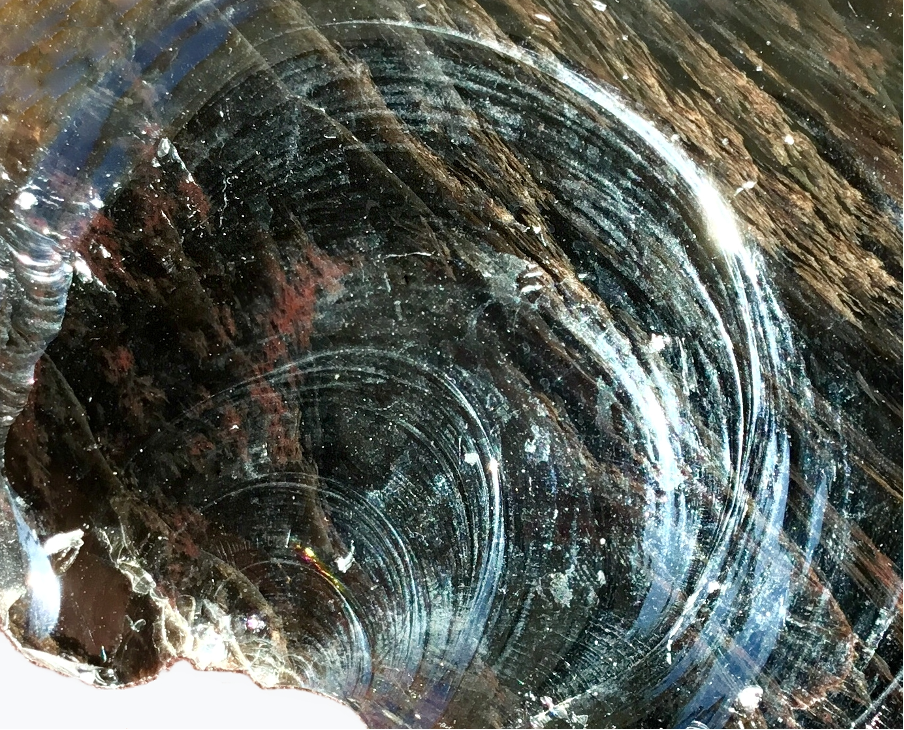

A distinctive feature of obsidian tools is the conchoidal shape of their fractures, characteristic of brittle materials. This type of fracture involves the formation of wavy, semi-curving surfaces that radiate in a direction opposite to the point of impact where mechanical force is applied. For archaeologists, these wave-like patterns record the gestures involved in the craftsmanship of stone tools — gestures that can be traced and reconstructed through close observation and detailed drawing. Such fractures are recognized as distinctly hominin, since they can only be produced through the application of mechanical force, unlike cracks caused by natural phenomena such as frost. When archaeologists encounter a sequence of conchoidal fractures created to produce sharp edges for scraping, cutting, or hunting, they recognize the mark of hominin presence.

Figure 2: Conchoidal fracture, Obsidian from Armenia. Ivan Petrovich Vtorov. Courtesy of Wikipedia Commons, CC-BY-SA-4.0

A key factor enabling these fractures in obsidian is the material’s less-than-solid properties. The conchoidal fracture, which allows archaeologists to reconstruct the craftsmanship of an obsidian tool, indicates that force propagates through the material in a wavelike pattern — a kind of fluidity that resonates with the unique molecular composition of glass. Obsidian is a naturally occurring volcanic glass formed with minimal crystallization. It is classified as an amorphous rock — a term often used interchangeably with ‘glassy’ to denote the absence of the orderly atomic structure found in crystalline materials. Challenging the conceptual framework of traditional materials science, glass resists categorical classification as either solid or liquid. Although apparently solid, the atoms and molecules in glass are arranged in ways that are nearly indistinguishable from those of a liquid. In contemporary materials science, glass is often defined negatively: as a solid in which atoms and molecules are disordered, like a liquid. Put differently, glass is also described as a “supercooled liquid,” meaning a liquid that remains below its melting point. Although imperceptible to the naked eye, the molecules in glass continue to move — albeit extremely slowly.[1]

Glass thus exemplifies what might be called a *solidfluid*: a material that defies the categorical thinking that has shaped Western logics of substance since classical antiquity (Ingold and Simonetti 2022). The formation of glass — and the question of why it appears solid despite behaving as a liquid — remains a mystery within materials science, primarily because its phase transition from molten to rigid deviates from typical thermodynamic behaviour. As we noticed already, glass molecules never align into a crystalline pattern, unlike substances such as ice, which serve as standard pedagogical model for distinguishing material states categorically, alongside water and vapour.[2] Instead, the molecules in glass merely slow down, retaining a disordered structure. Moreover, unlike again ice, glass does not release latent heat as it cools. Its transition to rigidity occurs not at a fixed temperature but depends entirely on the rate of cooling. Some scientists have speculated that if glass were cooled at an infinitely slow rate, it might solidify below absolute zero — potentially violating the third law of thermodynamics — producing what has been theorized as ‘ideal glass.’ This theoretical state reflects how the viscosity of glass is measured relative to the entropy — or disorder — of its molecular structure (Chang 1998).

Furthermore, the amorphous, fluid-like nature of glass has led some physicists to question whether it might challenge even the second law of thermodynamics. Specifically, no ‘arrow of time’ — or *material time* — can be definitively traced in the microscopic structure of glass (Böhmer et al. 2024). However, as geologist Marcia Bjornerud has noted, materials on Earth do not behave like the distilled substances studied in physics and chemistry laboratories; they are fundamentally historical. Indeed, as archaeological evidence shows, glass is not pure flow. At the human scale, volcanic glass preserves a memory of a more-than-liquid correspondence between matter and hominins, stretching back at least two million years. Obsidian behaves as neither solid nor fluid but as *viscous* — precisely because history endures in its material composition. After all, as philosopher Michel Serres (2009) reminds us, the *dure* (the hard) is meant to endure (*durée*); two notions that etymologically overlap in both Latin and Germanic languages.

Discussing this less-than-solid, more-than-fluid correspondence between humans and stone is far from trivial. Traditionally, stone tool production has been viewed in archaeology and related disciplines as a thermometer of human evolution — an activity supposedly driven exclusively by “men”. According to this narrative, it was man’s involvement in tool production that set humans apart from the rest of nature by developing mental capacities that eventually led to language. Man, the original designer, developed a capacity to conceive form and impose it onto raw matter, a doctrine known since Aristotle as *hylomorphism* — from the ancient Greek *hylē* (ὕλη) and *morphē* (μορφή), meaning ‘matter’ and ‘form’ respectively.[3] Correspondingly, prehistoric women have traditionally been relegated to gathering and domestic roles — activities presumed to be less visible in the archaeological record due to the poor preservation of organic materials. As feminist archaeologists have argued for decades, this binary division of labour between ‘man the hunter’ and ‘woman the gatherer’ reflects not an objective past but assumptions shaped by the intellectual milieu in which archaeologists operate (Conkey and Spector 1984). Ultimately, there is no empirical evidence proving that males were solely responsible for tool production or hunting (Gero 1991). Any effort to resolve this question definitively risks committing a *retrospective fallacy*, whereby scientific interpretations of the past are shaped by present-day values.[4]

This persistent binary echoes broader Western distinctions between solidity and fluidity, which are mirrored in a range of dualisms, most notably that between matter and spirit. These binaries underpin long-standing divisions between ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ forms of knowledge. In today’s professional contexts, for instance, business managers and academic administrators often distinguish between ‘hard skills’ (typically attributed to male workers and associated with formal knowledge and technical proficiency) and ‘soft skills’ (often attributed to female workers and associated with intuition and communication, socialised informally). Likewise, when policies are enacted to correct systemic gender injustices in increasingly fluid social landscapes, they are often framed in the language of ‘affirmative action’ — a phrase whose etymology suggests that modern society attempts to counter solidity with further forms of rigidity. This is unsurprising, given that the word ‘solidity’ derives from *solidus*, the Latin term for the coin used to pay Roman soldiers for their physical strength in battle — a legacy upon which Western intellectual traditions have long been built, in part under the influence of Ancient Greek philosophy.

As Henri Bergson (1998: ix) famously argued, a ‘logic of solids’ has dominated philosophy from Plato’s search for unchanging essences to the present day — a tendency he sought to reverse. For Bergson, reality is not composed of fixed entities to which change is subsequently added; rather, reality is fundamentally change. Perhaps Pleistocene humans had a more nuanced understanding of the fluidity of the material world — a world in which life, both human and non-human, continues to unfold, as it retains a memory of the past. This fluidity confronts us starkly in the current planetary crisis, as we recognize that the Earth on which human civilizations flourished during the Holocene has never been truly stable (Neil 2021). Climate, too, rests on a precarious balance — destabilized now arguably by Western narratives of human exceptionalism built on a masculine ability to impose his will onto passive matter.

In this context, we should remember that all matter on Earth is ultimately viscous — even the hardest stones, such as granite, will deform over geological time. This insight aligns with the field of rheology, founded in 1964 by Israeli scientist Marcus Reiner, who drew inspiration from the philosophy of Heraclitus and his dictum *panta rhei* (Πάντα ῥεῖ), meaning ‘everything flows.’ Rheology — the study of material flow, particularly in solids — rejects the notion that matter can be neatly divided into distinct categories. Solids, in this view, are simply extremely viscous fluids — an idea that aligns with geology’s perspective on matter. As Bjornerud eloquently puts it, ‘rocks are not nouns but verbs’ (2018: 8). From the vantage point of deep geological time, our human origins are not founded upon the masculine strength projected through narratives of human exceptionalism, but upon an enduring correspondence with *solidfluid* matter in constant becoming.

References

Böhmer, Till, Jan P. Gabriel, Lorenzo Costigliola et al. 2024. ‘Time reversibility during the ageing of materials,’ Nature Physics 20: 637–645.

Change, Kenneth. 1998. ‘The nature of glass remains anything but clear’, New York Times, 29 July: https://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/29/science/ 29glass.html.

Conkey, Margaret W. and Janet D. Spector. 1984. ‘Archaeology and the study of gender.’ Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory 7: 1-38.

Bergson, Henri. 1998. Creative Evolution. New York: Dover.

Bjornerud, Marcia 2018. Timefullness. How Thinking like a Geologist Can Help Save the World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Gero, Joan M. 1991. ‘Genderlithics. Women’s role in stone tool production,’ Joan M. Gero and Margaret W. Conkey (eds), Engendering Archaeology. Women in Prehistory, pp. 163-193. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Ingold, T. and Simonetti, C. 2022. ‘Introducing solid fluids.’ Theory, Culture & Society 39(2): 3-29.

Ingold, T. 2013. Making. Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. Abingdon: Routledge.

Méndez, César, Charles R. Stern, Amalia Nuevo Delaunay, Omar Reyes, Felipe Gutiérrez, and Francisco Mena. 2018. ‘Spatial and temporal distributions of exotic and local obsidians in Central Western Patagonia, southernmost South America.’ Quaternary International 468: 155-168.

Mussi, Margherita et al. 2023. ‘Early Homo erectus lived at high altitudes and produced both Oldowan and Acheulean tools.’ Science 382: 713-718.

Nail, Thomas. 2021. Theory of the Earth. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Simonetti, C. 2022. ‘Viscosity in matter, life and sociality. The case of glacial ice.’ Theory Culture and Society 39(2): 111-130.

Stern, Charles. 2018. ‘Obsidian sources and distribution in Patagonia, southernmost South America.’ Quaternary International 468: 190-205.

Zanotto, Edgar Dutra (1998) ‘Do cathedral glasses flow?’ American Journal of Physics 66: 392–395.