Hannah Knox is the Max Gluckman Professor of Social Anthropology at the University of Manchester, and writes on climate models and energy systems, smart infrastructures, data politics and governance and experimenting with how to incorporate sensory and environmental data into ethnographic description. Knox has recently published with Gemma John in 2022 the book Speaking for the Social: A Catalogue of Methods (Punctum Press) and in 2020 Thinking Like a Climate: Governing a City in Times of Environmental Change with Duke University Press.

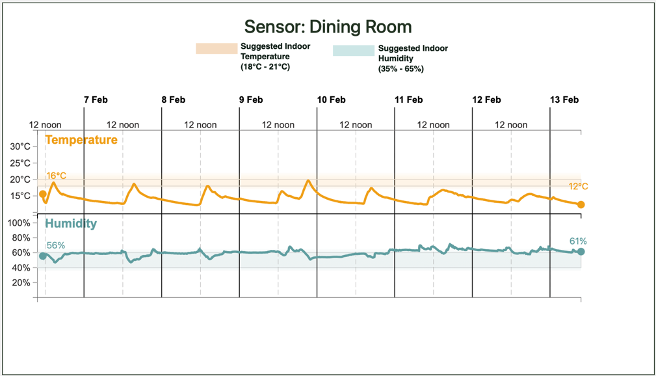

In this glossary entry I consider waves through the concept of thresholds. Thresholds are a common feature in descriptions of wave-like phenomena. They are concept-devices that indicate the point at which peaks or troughs in material arrangements are likely to cause transgressions to occur. For example, thresholds are used to indicate when river levels are likely to overflow, when air pollution concentrations might tip into health emergencies, or when disease prevalence will put intolerable pressure on health services. Thresholds appeared in my research when I became involved in a project exploring the role of visualisations of temperature and humidity data as a way of mediating collective conversations about the challenges of cold and damp in UK homes. As part of the research project, we generated visual depictions of the fluctuations of temperature and humidity, across a week-long period, within the homes of 26 participants based in London and Greater Manchester. My colleagues, Georgia and Mike,[1] who designed the visualisations, included in the graphs two ‘threshold’ bars – one overlayed on the temperature chart in a light shade of orange, and the other overlayed on the humidity charts in green-blue.

Fig 1. A visualisation of temperature and humidity, including bars indicating the thresholds of suggested healthy temperature and humidity.

These threshold bars were noted by some of the research participants during a series of workshops we held when we discussed the data we had collected:

Joe: Yeah so, I’m Joe, I live on this street. I live with my wife in a three-bed flat on the top floor. I’ve not lived here even a year yet. I think as I said in the initial interview what attracted me to it was just learning more about, I guess, some of the history of the property and as a new first-time homeowner the areas that I needed to focus on. So, I was surprised to see that, I think, every single day of the week – I don’t think there were many points where I hit the healthy recommended range for either temperature or humidity, despite it feeling like I was setting fire to my bank account to heat the flat – which is to be expected to a certain extent with an old property.

Chris: I foolishly put my sensor for the kitchen right above the hob. I’ve got a little shelf and the kitchen is really, really small. But I was interested there, the humidity spikes and then as soon as I’m done cooking it returns right back to base level. So, it’s up pretty high but the humidity there has stayed very, very, very consistent. Yeah, I’d probably say some of the other little spikes I’ve got are like boiling the kettle beneath it and stuff. But then that consistent [humidity] is maybe early 40’s, mid 50’s. I can’t remember whether or not that’s a good thing or a bad thing.

Matt: It’s pretty good. [Laughs]

Hannah: It sounds pretty good.

Matt: Yeah, I think between 40 and 60 is the ideal.

Chris: It’s slightly shaded.

Georgia: No, I think he has a different version.

Chris: Oh yeah, I do have a different one.

Matt: Yeah 40 to 60 is the normal range.

Chris: Nice.

People reflected on their own data in relation to these threshold bars. It prompted them to consider whether their homes were doing well or badly according to the normative suggestion that these bars put forward. Whilst no one questioned the veracity of the measures of temperature and humidity detected by the sensors, they did query the status of the threshold bars which framed the temperature and humidity levels in their homes within a normative and normalising structure of generically appropriate guidelines for homeowners. These sat in contrast with the specific experiences of heating (‘setting fire to my bank account’) and humidity (“I’ve not noticed any damp yet. I do have a dehumidifier which I use in the winter. Do you want me to refrain from using that during the study?”) where the normative value of these activities was not self-evident.

In this glossary entry I delve into the relationship between the waves we depicted and the thresholds they invited. I start by considering what kinds of ‘waves’ we are talking about here, before exploring the way that these kinds of waves draw forth ‘thresholding’ as a practice. From here I delve into the question of what a threshold is in this context, what it is hoped it will do, and what some of the challenges of thresholds are, before returning to our decision to include thresholds in our visualisations of the data we collected.

Waves that invite thresholds

First then, a note on waves. The kinds of waves that we are suggesting invite thresholding practices are those that are made evident through measurement and subsequent representation in line graphs. Graphs of this kind make visible waves by plotting material changes over time or space. The wave-like form that emerged from our temperature and humidity monitoring was not experienced outside its representation in data, as ‘wavy’. People knew when their houses were cold (‘I put a jumper on’, ‘I turn on the heating’, ‘I use a hair dryer to warm my feet’), and when they were humid (‘I open the windows to air the house every morning’, ‘we always keep the bathroom window open even in the winter as it stops the mould’). However, none of the participants used the notion of the wave in pre-workshop interviews, to describe their experiences of temperature and humidity at home.

It was only when the data was plotted over the week-long period of data collection that the wave-like properties of temperature and humidity appeared. A particularly spikey graph measuring the temperature in a sunny conservatory, was described in one workshop as “your house is having a heart attack!”. In another, a participant commented “here’s like one spike on mine where the heating went up and the humidity went down at exactly the correlating times”. Here the linked spike-and-trough introduced new insights about the interrelationship between temperature and humidity. The depiction of measurable materialities as a wave like phenomenon revealed ebbing and flowing thermodynamic relations that were rarely discerned otherwise.

It was this kind of slow, elongated, magnitudinal wave of material relations shifting over time – which we subsequently depicted in line graphs as the magnitude of change over time – that invited the possibility that there might be a point where these fluctuations might be too high or too low. This is where the idea of the threshold entered the picture.

Thresholds

The primary dictionary definition of the threshold is a wooden or stone plinth that separates the outside of the home from the inside.[2] In this meaning, to cross over the threshold is to enter from a public to a private domain. Whilst it marks a crossing point, one might imagine that the move to an interior space would be an entry into a realm of safety. However, with the thresholds that we are exploring here, they tend to indicate conversely, a movement into a zone of danger.

Where temperature and humidity are concerned, thresholds of maximum and minimum recommended levels are indices of probabilities where harm may occur. In the UK, where we did our research, Public Health England (PHE) recommends indoor air temperature thresholds of 18-21∞C.[3] A systematic literature review commissioned by PHE in 2014, reinforced the relevance of such a threshold, highlighting some evidence of the impact of temperatures of less than 18∞C on raised blood pressure and risk of blood clotting, particularly among older people (Jevons, et al. 2016).

One thing however, that is particularly intriguing about this literature review, is that the evidence underpinning this rather definite sounding threshold is remarkably weak. The authors state that studies of the impact of air temperature on health are few and far between (ibid: 6), meanwhile factors such as how much people move, age, gender and health all have an effect on the relationship between temperature and health (ibid: 54). Nonetheless in spite of the heavily caveated tone of the systematic review, the PHE recommended temperature threshold is used extensively as a guideline for how much people should be heating their homes, and for establishing standards for home building and renovation.

This systematic review points to the complexity of establishing a threshold as a definitive measure of relations. To understand this in more detail, it is helpful to refer to long running debates within another discipline that has possibly done the most to theorise and think through the notion of thresholds in the way we are describing them – the discipline of psychology.[4]

Thresholds have long been discussed in psychology with regards to deliberations about the nature of perception. In a 1963 paper entitled ‘The Threshold Concept’, the utility of the idea of the threshold within the discipline was discussed at length (Corso 1963). Here the problem in hand has been how to understand the boundary between sensory stimulus and the mind’s conscious reaction to that sensory stimulus. The threshold was initially introduced to point to the boundary between unconscious sensing and a conscious response, that is ‘the boundary which an idea appears to cross as it passes from the totally inhibited state into some (any) degree of actual ideation” ((Herbart 1824) cited in (Corso 1963)).

Corso’s essay charts the promise of the threshold concept and also outlines its limitations. For our purposes are few points are particularly notable. First, in psychology, it becomes clear early on that adjudicating probabilistically the relationship between two states (non-perception and perception) is highly problematic. Early attempts at identifying the absolute threshold between stimulus input and perception was arrived at probabilistically – with the threshold measure for the perceptibility of a particular stimulus being a ‘stimulus that arouses a response 50 percept of the time”. The problem with this is that this meant there were some subjects who would experience a stimulus at a strength below the established threshold level – something that was patently absurd (how can you have a threshold for perception that allows for perception below the threshold?). Similarly, though, when it comes to temperature and humidity, we also saw that there were those who experienced negative effects of cold and damp even though their homes were ostensibly within the threshold range. By creating a concrete boundary, thresholds invite exclusions which then inhabit an unstable or awkward ontological position.

Second the threshold concept as discussed by Corso, struggles with the relationship between the notion of a sudden step change and a gradual continuum. Building on this, a third observation is that external factors complicate the idea of a simple relationship between cause and effect: ‘the same stimulus, even when applied in the same manner was sensed more or less strongly by one observer than another, and by the same observer at different times”. (Corso 361) Again we saw this in our own research, where different people experienced that category of ‘cold’ and even ‘mould’ radically differently depending on biographical, historical and cultural experiences:

Steve: “We do have like a lot of mould. And like I say, I grew up with it. So, when my landlord was being a bit weird about it, I was like, trust me. I’m not gonna be one of those tenants that is going to have a problem with it. I grew up in the 80s, on a council estate, so I’m used to it.

Ultimately these reflections from psychology demonstrate the threshold to be an epistemologically problematic concept, reifying what is in fact a complex and shifting interplay of internal and external relations into a singular hinge point between two different states (perceived/non-perceived or healthy/non-healthy).

Also providing a critique of the threshold concept, but from a more political set of concerns, Liboiron et al (2018) have recently written on problems with thresholds. They also highlight that the relations which thresholds purport to describe are far from simple descriptions of a hinge between one appropriate set of balanced relations, and another more unruly or problematic state of being.[5] In a study of toxicity and chemical exposure, they write that their interest is to “move concepts of toxicity away from fetishized and evidentiary regimes premised on wayward molecules behaving badly, so that toxicity can be understood in terms of reproductions of power and justice”. We might apply the same logic to thresholds of temperature and humidity or indeed any other thresholds that we find deployed to adjudicate ebbing and flowing material relations. With regard to temperature and humidity, this would demand we ask not what is the appropriate threshold of temperature and humidity within which people should live their lives, but rather what are the conditions within which cold and damp are systemically and actively produced and allowed to endure for some and not for others. It would move attention away from the question of whether people are themselves responsible for achieving thermal norms, towards the question of what classed and racialised assumptions might be at play in a class inflected tolerance/intolerance of damp and mouldy homes.

Thresholds are problematic then, but can they also be generative? The aim of our temperature and humidity workshops was not to arrive a definitive description of appropriate or inappropriate levels of temperature and humidity, but rather to provoke a dialogic engagement with these qualities when depicted as waves in graphic form. As we have seen, thresholds are common in evaluations of temperature and humidity levels. They are a vernacular cultural representation in this domain, deployed by housing associations, landlords and governments in conversations with citizens. To include them as objective indicators or normative descriptors has its obvious problems. But at the same time their limitation might also their strength. Legible, because of their reductionism, to organisations that utilise them to adjudicate questions of entitlement and harm, thresholds hold the possibility of being boundary objects through which novel political claims might be effectively made. Our suggestion for wave studies is that thresholds be recognised not only for what they are – tools of epistemological taming, power and control; but also for what they could be – boundary objects that might be mobilised, counter-politically, as powerful techniques for claim making within worlds that are constituted through ongoing socio-material fluctuation.

References

Corso, John F. 1963 A theoretico-historical review of the threshold concept. Psychological bulletin 60(4):356-370.

Herbart, J. F. 1824 Psychologie als Wissenschaft, neu gegrundet auf Erfahrung, Metaphysik, und Mathematik. Kb’nisburg, Germany: Unzer.

Jevons, R., et al. 2016 Minimum indoor temperature threshold recommendations for English homes in winter – A systematic review. Public health (London) 136:4-12.

Murphy, Michelle 2006 Sick building syndrome and the problem of uncertainty : environmental politics, technoscience, and women workers. Durham N.C.: Duke University Press.

Panagiotidou, Georgia, et al. 2023 Supporting Solar Energy Coordination among Communities. Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies 7(2):1-23.

Petryna, Adriana 2022 Horizon work : at the edges of knowledge in an age of runaway climate change. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Samanani, Farhan, et al. 2025 Everyday laboratories: Collective speculation and energy futures. Futures : the journal of policy, planning and futures studies 170:103594.