Safety concerns and security measures are key to understanding how people feel affected by artificial light at night. In controversies over light levels, the argument of public safety regularly triumphs over environmental concerns about light pollution. Yet, unravelling the relationship between light, safety and security is all but simple as light waves interact with human gut feeling and, at the same time, produce societal, biological and ecological side-effects that go well beyond security lighting.

The following text explores these entanglements from a social scientific perspective. It is based on a keynote presentation during the Artificial Light At Night conference (ALAN) on August 11 2023 in Calgary, Canada. The ALAN expert audience is well familiar with fighting myths as well as bad practice in safety and security lighting. Therefore, my aim was not primarily to provide new evidence, but to offer novel perspectives and some food for thought. To start with, my proposition is to take fears of darkness and light for the sake and sense of safety serious as a starting point for exploring the relation between light and safety in more detail. Telling people not to be afraid in the dark when they feel that way, and denying them light, may not help mutual understanding. However, and as outlined below, in the face of biodiversity loss and climate change it might still be a good idea to expand our notion of safety beyond anthropocentric perspectives and challenge outdated and even misleading assumptions about how lighting might reduce road accidents, crime and gendered ‘female’ fears. I will therefore end with an invitation to think light and darkness, safety and security in a more cosmopolitical way. By thinking in this way, we may be able to find lighting solutions that provide safe street lighting and a sense of security in public spaces without compromising the wellbeing of living species through excessive anthropogenic light emissions.

Security lighting – a powerful paradigm

In the past, artificial light at night has developed and continuously increased in response to a variety of human demands. Histories of artificial light at night offer great insights into who needs light at night and why. What we can learn from these histories, is that in pre-industrial cities illuminating the streets with oil lanterns was extremely expensive and therefore not only a security measure, but also a means of representing state power or wealth (Brox 2010; Schivelbusch 1988).

In other words, safety did not come first in the history of urban lighting. Instead, merchants and Baroque kings were the ones that first illuminated European cities in the 17th century for their profit, for representative reasons or for leisure (Koslofsky 2011). In the course of the 20th century however, electric street lighting developed into a taken-for-granted urban infrastructure. Safety considerations provided the basis for developing road lighting standards. Today, security and safety arguments are the dominant paradigm that explains why we illuminate outdoor spaces at night. Yet, how means (lighting) and ends (safety) are linked is not always spelled out.

There are not only different kinds of more and less-effective lighting, but also different kinds of safety. In particular, we can distinguish between a) physical needs, such as orientation light, b) social needs allowing people to see each other and be seen and c) psychological needs, i.e. a more or less well-grounded unease or fears of dark urban spaces. The following three sections sketch out the respective arguments and their shortcomings.

Mind the steps – orientation and road safety

The problem of how to see despite darkness and how to avoid glare are key to safety considerations in public lighting. Sometimes pictures say more than words. These photographs taken by Christopher Kyba in Potsdam, Germany, nicely illustrate how lighting can be installed in ways that make public staircases unsafe (left), rather than safer (right). If the lighting is well done, we can actually see the stairs and where we are going. In contrast, blinding lights have the opposite effect.

Photo: Christopher Kyba CC BY 4.0.

Physical needs of light in the dark have not always been the same, but responded to changing contexts. Since the late 19th century, the speed at which we move through dark outdoor spaces has increased enormously. In particular, automobility has prompted a transformation of nocturnal lightscapes – a co-evolution of outdoor lighting and motorised traffic (Jakle 2001). As historian Sandy Isenstadt (2018) outlines in beautiful detail, speeding that is, driving fast at night, became a real hobby in the early 20th century. Obvisously, this caused new problems. Not only wild animals, but also pedestrians were in great danger of being blinded by the headlights of cars racing through the night… Accordingly, homogeneous lighting became a matter of scientific study. To ensure traffic safety despit high speeds, engineers began to calculate visibility. A key challenge was to determine the right spacing between light poles in order to avoid black zones on the street and to design car headlamps in relation to braking distances and driver reaction times (Mosser 2007: 31).

Today, statistical evidence suggests that street lighting indeed reduces the number of accidents in the dark (Wanvik 2009: 124). However, studies also reveal that these positive effects depend on the quality of light fixtures and how well the lighting is adapted to the specific spatial situation. For instance, lighting a busy intersection in the early evening when people drive home from work while also pedestrians, including children are still on the street has shown positive effects (Pauen-Höppner 2013).

In contrast, lighting an empty main road after midnight might encourage drivers to drive faster. Dark sky proponent and statistic expert Paul Marchant points to important confounding factors like road-specific traffic volumes and general trend towards better road safety, also due to safer cars, that might explain why accident numbers are decreasing irrespective of lighting. Statistical correlations are not the same as cause-effect relations (Marchant, et al. 2020: 467).

Seeing and being seen – lighting for social control

You have probably seen this picture before… Security lighting – making sure that you will notice anyone who wants to enter your property… Well… Well meant is not well-done.

To be seen or not to be seen is important not only in the context of road safety, but also to be and feel safe in the company of other people – friends and foes. Again, this photocollage by George Fleenor nicely illustrates the myth of lighting as a private security measure. The problems of this blinding lighting fixture are quite obvious, so let’s move on to social theories and philosophies of seeing and being seen. In his book “Disenchanted night” on the industrialization of the night, historian Wolfgang Schivelbusch outlines how Gaston Bachelard, in his ‘poetic of space’ describes – I quote “the process of surveillance, counter-surveillance and mutual surveillance that is set in motion when a lantern is lit. Anyone who is in the dark and sees a light in the distance […] extinguishes his own lantern so that he is not exposed defenseless to the gaze of the other…” (quoted in Schivelbusch, 1988: 5-97).

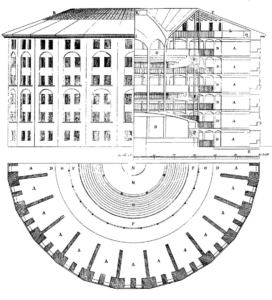

The sociologist Michel Foucault has elaborated on this point in his seminal work “Surveiller and punir” (1975). In a nutshell and in my words, he argues that socio-spatial arrangements of modern governance discipline human subjects by letting them know and feel that they are observed by the state at any time. His iconic example is the panopticon which the British philosopher Jeremy Bentham proposed as the perfect building form for a prison. All prisoners are under surveillance as the guards at the centre can look into all cells.

This plan of Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon prison was drawn by Willey Reveley in 1791.

In the same vein, municipalities argue that better facial recognition can reduce crime as perpetrators will be better recognisable and they will also know it. This is why brighter and white lights with a better colour rendering seem a perfect security measure. The L.A. Bureau of Streetlighting used that argument, too, when they installed bright LEDs throughout the city, primarily in order to save energy. But, and that is anecdotal evidence, I know from my field research there that not all people liked it – arguing that the cool-white was terrible, the light levels too high and the cut-off too harsh causing neighbours to install more security lights in their front yards as their porches looked even darker next to the blinding streetlights. The ambivalent reaction to the L.A. streetlights corresponds with scientific studies that show inconclusive evidence regarding the causal relation between more lighting and less crime.

The British criminologists Welsh and Farrington outline “two main theories of why improved street lighting may cause a reduction in crime.” (2008: 1) The first is about deterrence. It suggests that improved lighting leads to increased surveillance, keeping offenders from committing their crimes. The second suggests that improved public lighting has a positive effect on community pride, signalling the people in a neighbourhood that they are worth an investment in infrastructure. In line with that Casper Laign Ebbensgaard observed that people in neighbourhoods where streetlights had not been upgraded to LEDs reckoned that the municipality cared less about their community than about neighbouring district. These findings are not trivial as they correspond with more general social-scientific theories and findings.

Broken Windows, Photo: CC0.

The “broken Windows Theory” suggests that neighbourhoods can enter a ‚downward spiral‘ and loose positive social control if broken windows, graffiti on walls and dirt on streets signal communal neglect and a lack of order and law enforcement (Kelling and Wilson 1982). Similarly, the sociologist Jane Jacobs coined the slogan “eyes on the street” to describe positive social control in urban public spaces which she found wanting in big U.S. cities (1961). Obviously, eyes on the street are more effective if public spaces are illuminated after dark. Yet, there is no causal relationship between more safety thanks to social control and security lighting. Instead, we might observe self-reinforcing effects or an upward spiral: Where people feel safe in night-time streets, they are more likely to go out at night adding to the “eyes on the street”. Again, lighting can contribute to this upward spiral by making urban spaces look cosy or attractive. However, they will not make these places safer if, for example, one social group decides to control their street in a xenophobic or homophobic way.

At this point, we can note: There is no direct causal link between light and safety. Nevertheless, urban security often start and end with a call for more light, as criminologist and urban consultant Dunja Storp suggested in a recent conversation. So why is that? The most plausible explanation is that urban planning and policy decisions respond to fears rather than facts.

Fearing darkness – lighting for a sense of security

Fears in the dark seem deep-seated in humans. They are closely related to a fear of losing control in a potentially dangerous or hostile environment. We just feel safer when we see our surroundings since we very much depend on our visual sense for orientation. When it comes to spotting obstacles and threats, artificial lighting is a relief. Yet, bright lights will not eliminate the causes of societal fears – not everywhere and not for everyone. On the contrary, darkness has always been a protective veil for people and groups for whom ‘eyes on the street’ might create more problems than safety. Moreover, vulnerable groups often feel uncomfortably exposed when walking on an illuminated path surrounded by darkness. Walking in the spotlight makes it impossible to see a person standing in the dark. In public debates however, these nuances and the difference between actual safety issues and a felt lack of security get often blurred. Brighter lighting is therefore a popular response to a perceived lack of safety. It is also a common response to tackling Angsträume – a German urban term for ‘spaces of fear’. Unfortunately, not every underpass looks better if it is properly lit (see image below).

Such spatial design measures are often discussed and implemented in the name of women with an explicit reference to female fears in the dark. A 2011 Gallup report suggests that there is a “pronounced gender gap in Europe, the global region with the greatest share of high-income countries” when it comes to women’s and men’s sense of safety in public spaces. More precisely: among all European countries studied, two thirds of men said they felt safe walking alone at night, but only just more than half of the women represented in this survey. This data was also referenced in a recent OECD report.

Another UK survey published in August 2021 reveals that one in two women felt unsafe in public spaces after dark, whether it was a quiet street near their home or a busy public place. However, I could not find any further information on how these surveys were conducted and in what context.

Critical thinkers like the sociologist Renate Ruhne (2020: 431) have problematised gendered discussions about women’s insecurity as a “powerful historical construction” that has the performative effect of making women feel unsafe and thus inscribes inequalities in urban public spaces.

The German sociologist also highlights the public misconception that women are particularly vulnerable in public spaces. In contrast, statistical analyses show that men are more likely to get into trouble or be assaulted in public spaces, while violence against women is more likely to happen in their homes that is, in private spaces. Along this line, a French sociological study concludes that more differentiated approaches are needed:

“it is necessary to explore in finer detail the context associated with these fears. […] In contrast to macrosocial approaches, which stress the gap between victimization rate and fear levels, an individualized approach shows that fear is fueled by the possible experience of victimization.” (Condon et al. 2007: 102-103)

Similar points were made by a female expert group that I interviewed about the topic (Schulte-Römer 2023). All four are used to be outside at night and they refute the generalised assumption of female anxieties as an argument for more lighting. In the course of the discussion, night-time advocate Sabine Frank criticised that crime scene movies reproduce such anxieties by using dark outdoor spaces for creating suspense, while municipal decision makers repeat that light means security. In her opinion this ‘populist bogus’ prevents us from seeing the real problems. By “real problems” the amateur astronomer means not only that humans lose the opportunity to observe the night sky, but also the impact of artificial light at night on living species and ecosystems.

Keeping light emissions within a ‘safe operating space’?

In recent years, the safety paradigm of lighting has come under pressure. On the one hand, climate policies set incentives for reducing energy consumption. In Europe, the energy crisis of the Russian-Ukrainian war led municipalities to an unprecedented reduction of public lighting. On the other hand, scientists’ warnings about anthropogenic light emissions are getting louder. Their research shows that the world is getting brighter and brighter at night and that anthropogenic lighting at night affects the behaviour and day-and-night-rhythm of all living species, including plants and humans. Through the ecological lens, the loss of night-time darkness appears as yet another feature of the Anthropocene (Durmus 2024). Light at the wrong place at the wrong time disturbs the natural circadian rhythm of living species and ecosystems. These effects include humans. Especially in cities, people feel disturbed by outdoor lighting that falls into bedroom windows and disturbs their sleep. And I know several people, including myself, who only became aware of this nuisance after hearing about ‘light pollution’. Satellite images show that the night on Earth produces light emissions that travel far into space.

So, what if we take the scientists’ warnings and climate change serious and think about light, safety and security beyond stereotypes and taken-for-granted light levels, beyond human fears, crime prevention and road safety? How can we include non-human needs for light and darkness in light planning practices? One way to address this question would be to define what environmental scientists call a “safe operating space for humanity” based on systemic analyses and cross-sectoral modelling of “planetary boundaries”. Following this logic, we could argue that our short-sighted hunger for light is endangering the very basis of our existence by decimating biodiversity, especially insects.

However, this science-based approach would imply that ALAN research could identify the relevant thresholds and tipping points that mark the points at which ALAN irrevocably disrupts a given ecosystem. To my knowledge, such limit values do not yet exist and are also difficult to establish. Living species not only react to very low light levels, but are also sensitive to different light frequencies. As a result, all anthropogenic lighting above zero is likely to have an effect on nocturnal ecosystems. But will these effects be harmful? To justify risk management of lighting, policy-makers would surely ask this question and demand scientifically robust evidence that lighting not only affects the behaviour of living species, but actually causes harm in the form of cell damage, disease or even death. As far as I am aware, such evidence does not (yet) exist (Schröter-Schlaack 2020). People who fight hard to preserve dark skies despite increasing light emissions worldwide might respond: Do you need scientific proof in order to listen to our common sense? Isn’t there enough scope for improvement – energy savings thanks to better lighting, better sleep and hybernation for everyone, including flora and fauna, visibility of the starry sky – that we could explore right now without further delay? I think we can, but it requires a discussion about what constitutes ‘common sense’.

A cosmopolitical proposal for good lighting

In her book, “Making Sense in Common” Belgian philosopher Isabelle Stengers writes about the challenge of allowing common sense to prevail. Letting common sense prevail requires the hard work of recognising the knowledge of others and acknowledging perspectives that are different from our own. It requires sharing rather than relying on abstract scientific facts to arbitrate in situations where incompatible interests clash. In our particular context, could mean: Resisting the reflex to equate light with safety. Pausing to consider the value of darkness. Considering the possibility that not all species on Eearth need light at night and might even feel disturbed by it. Switching off lights that are not needed to produce a win-win situation (reduced energy consumption and reduced emissions).

Finally, changing lighting practice in that way would also resonate with what Isabelle Stengers calls a ‘cosmopolitical proposal’ (Stengers 2015, 994-95), meaning a politics that allows for a ‘cosmos’, a ‘good common world’. Such politics invite us to slow down, reconsider what we take for granted (e.g. the necessity of illuminations all night long), double-check what we think we know and how we generalise (e.g. ‘light equals safety’), think beyond our personal interests and needs (e.g. I am used to light, I want to keep it), acknoweldge others’ interests and needs (e.g. my neighbours prefer darkness and insects die in my lights), and to create spaces for hesitation and discussion about what it means to say ‘good’. I dare say, a cosmopolitical approach to artificial light could draw attention to the value of darkness (Edensor 2017) and help maintain what Nick Dunn (2020) describes as ‘nocturnal commons’ without dismissing security concerns and anxieties. It could also open up a space to revise common lighting practices that once offered solutions to 20th century problems and, to date, incorporate physical and engineering knowledge, but little biology, and may reproduce historical inequalities (Le Gallic and Pritchard 2019). A cosmopolitical approach would certainly prevent us from essentialising one standard ‘safe’ way of lighting and instead, encourage debate about what constitutes good lighting and safety in a given situation.

Finally, a cosmopolitical proposal challenges us to make tensions explicit. If light had no negative side effects, we could fully illuminate our surroundings, banish all shadows at night and be forever safe and happy ever after. This does not seem to be the case – and lighting designers would not recommend it for aesthetical reasons (Narboni 2009). Since light orchestrates the day and night rhythm of life on Earth, the addition of artificial light at night (ALAN) inevitably affects the synchronisation of biological and social processes – and there are also good cultural reasons to preserve the darkness, e.g. to admire the night sky. So I wonder, in the WAVEMATTERS project and beyond, how feel people affected by the positive and negative effects of light? How does common sense change with regard to what we consider as ‘good lighting’? From urban spaces of fear to planetary boundaries, what scale are we talking about now and in the future when we say ‘better safe than sorry’?

References

Brox, J. (2010). Brilliant: the evolution of artificial light. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Dunn, N. (2020). Dark design: A new framework for advocacy and creativity for the nocturnal commons. The International Journal of Design in Society, 14(4), 19.

Durmus, D. (2024). Opinion: Embracing ‘anthropogenic’over ‘artificial’light at night. Lighting Research & Technology, 56(3), 309-310.

Ekirch, A. R. (2006). At day’s close: night in times past. WW Norton & Company.

Isenstadt, S. (2018). Electric Light: An Architectural History. MIT Press.

Jackle, J. A. (2001). City Lights: Illuminating the American Night (Landscapes of the Night). Johns Hopkins University Press

Jacobs, J. (1961). Life and Death of Great American Cities. Random House. New York City

Koslofsky C. (2011). Evening’s Empire: A History of the Night in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge University Press

Narboni, R. (2009). La nuit disparue. Florence: Targetti Foundation Publishers.

Pauen-Höppner, U. and M. Höppner (2013). Öffentliche Beleuchtung – mehr Licht heißt nicht mehr Sicherheit, in: M. Held / F. Hölker / B. Jessel (Hrsg.), Schutz der Nacht – Lichtverschmutzung, Biodiversität und Nachtlandschaft, BfN-Skripten 336, Bonn: Bundesamt für Naturschutz, 105-108.

Ruhne, R. (2020). Urbane ‚Angsträume’ – Die Stadt als ein vergeschlechtlichtes Bedrohungsszenario, in:

I. Breckner et al. (Hrsg.), Stadtsoziologie und Stadtentwicklung: Handbuch für Wissenschaft und Praxis,

Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Schivelbusch, W. (1988). Disenchanted night: The industrialization of light in the nineteenth century, trans. Angela Davies. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Schröter-Schlaack, C., Revermann, C., & Schulte-Römer, N. (2020). Lichtverschmutzung–Ausmaß, gesellschaftliche und ökologische Auswirkungen sowie Handlungsansätze. Endbericht zum TA-Projekt. Berlin: TAB – Büro für Technikfolgen-Abschätzung beim Deutschen Bundestag.

Schulte-Römer, N. (2023). Who is afraid under dark skies? Four female experts on” spaces of fear”, astronomy, and the loss of the night: a group discussion with Sabine Frank, Josefine Liebisch. Dark Skies: Places, Practices, Communities, 177-188.

Welsh, B. C., & Farrington, D. P. (2008). Effects of improved street lighting on crime. Campbell systematic reviews, 4(1), 1-51.