This is an instalment of the Waves Classics on Henri Bergson’s Matter and Memory. It was first published in 1896. A book written very much in response to contemporaneous physics and other scientific problems, and in particular, the then development of “wave theory.” Louis de Broglie, an “originator” of wave theory of matter in France, claimed that Bergson “foresaw” some tenets of wave theory and quantum mechanics in his concept of duration and his critique of the mechanistic worldview of matter.

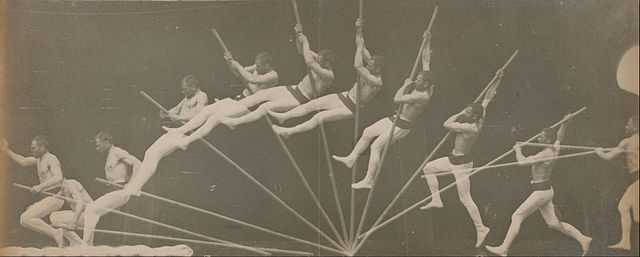

Movements with a pole, Foto: Étienne-Jules Marey, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Henri Bergson – could it not be argued that he is the thinker of the wave par excellence? Vibrations, durations, oscillations, tendencies, the elan vital, flows, fluxes, pure movement. He takes us away from the mechanistic worldview along with its own particular materialism, away from its vision of the physical world that places the contained within containers like so many well-arranged objects, of billiard balls as cause and effect, of a homogenous space-time that subtends physical solid objects, and away from those outlined solid objects that stand on their own in “simple locations”. At the beginning of Creative Evolution, Bergson writes, “We shall see that the human intellect feels at home among inanimate objects, more especially among solids, where our action finds its fulcrum and our industry its tools; that our concepts have been formed on the model of solids; that our logic is, pre-eminently, the logic of solids [………] . But from this it must also follow that our thought in its purely logical form, is incapable of presenting the true nature of life, the full meaning of evolutionary movement” (1922: ix-x). If we want to see the “true nature of life”, we must, it seems, dissolve solids, but, not into even smaller particles, which is just so many smaller solids, but to think outside of the logic of the solid itself – to turn to the liquid, the gaseous, the atmospheric, the diffuse. In a book equally interested in Life, in that elan vital, in the movements of taking shape, but without recourse to the unit, the one, or to grounds, foundations, and solids, but in multiplicities, movements and turbulences, Michel Serres writes in Genesis: “The very request for a foundation, for existential or gnoseological foundation, implies that one does not dig or lay a foundation in water or on the wind. Bergson is thus right to say that our metaphysics are metaphorics of the solid. The solid, then, is nothing else but the unit of multiplicities, a unit applied to or found by or for a large population. Thus, a concept is a solid and the solid is already a concept. We were afraid of gases and liquids, we understood nothing in Lucretius, our knowledge was not made for the great multiplicities [………]. We were afraid of wind and waters, we are now afraid of disorder and the rarely predictable. In fact, we are afraid of multiplicities [………]. The solid is the multiple reduced to the unitary” (1995: 108).

Who is afraid of wind and water? The water with its roaring multiplicity, and the chill of the wind: in the dizziness that accompanies a loss of static frames, solid grounds, and outlines – in the blur – how do you capture the wind? Italo Calvino’s Mr. Palomar standing in the sea tries to capture a wave: “he tries to limit his field of observation; if he bears in mind a square zone of, say, ten meters of shore by ten meters of sea, he can carry out an inventory of all the wave-movements that are repeated with varying frequency within a given time-interval. The hard thing is to fix the boundaries of this zone, because if, for example, he considers as the side farthest from him the outstanding line of an advancing wave, as this line approaches him and rises it hides form his eyes everything behind it; and thus the space under examination is overturned and at the same time crushed.” After trying to fit the waves into his abstract space, they continue to overflow them, eventually “he feels a slight dizziness”, “the stubbornness that drives the waves towards the shore wins the match: in fact, the waves have swelled considerably. Is the wind about to change? It would be disastrous if the image that Mr. Palomar has succeeded painstakingly in putting together were to shatter and be lost”. Failing to contain the waves, he loses patience: “Mr Palomar goes off along the beach, tense and nervous as when he came, and even more unsure about everything”. The mechanistic philosopher, Mr. Palomar, in his attempt to mathematise and geometricize the wave, a little like Leibniz, feels dizzy, lost in the confusion.

Bergson’s Matter and Memory is a good place to start to come face-to-face with our epistemic fear of the uproarious water and wind, especially Chapter IV where he formulates a vibrating theory of matter. He does this in reference to some physicists: Clerk-Maxwell, Lord Kelvin, and Faraday. Louis de Broglie, the originator of the wave theory of matter, in an essay called “The Concepts of Contemporary Physics and Bergson’s Ideas on Time and Motion”, writes, how, despite antedating quantum physics and material wave dynamics by forty years, Bergson’s ideas are nevertheless “quite close” to them.

So: Back to the movements themselves! On page 260 and 261, Bergson asks, “Whence comes then the irresistible tendency to set up a material universe that is discontinuous, composed of bodies which have clearly defined outlines and change their place, that is, their relation with each other?” Indeed. This is a way of organising the world into one of a “still life,” nature morte. For him, this is done to get things done. We need to organise things in ways in which they can be measured. They need to be “freeze-framed,” locatable in space and time. However, this ignores real movement and continuity, where things are not “in outline” but blend and melt together at their edges, where things come together in currents and streams, where rather than “things” – which for him are mere slowed down movements – there are vibrations and fluxes, composites and blurs. Things are but traces of movement, a residuum, a coagulation, a build-up. Bergson’s philosophy, perhaps, is a plea to move from a worldview of solids, of res extensa, of partes extra partes, of an organisation of matter in homogenous space, measured through quantitative means to a view of movements, of speeds and slownesses, of intensities and qualities, where there is no support or medium for change. On page 259, he writes: “all division of matter into independent bodies with absolutely determined outlines is an artificial division”. And again, on page 270: “Motionless on the surface, in its very depth it [matter] lives and vibrates”. There is a universal continuum of things, disturbances, movements, oscillations: confusion and obscurity, variations of energetic flows within fields of potentiality; things that tend to be, but not necessarily……….

In fact, he gives us some steps to follow to “obtain a vision of matter”:

“Try, first, to connect the discontinuous objects of daily experience; then resolve the motionless continuity of their qualities into vibrations on the spot; finally, fix your attention on these movements by abstracting from the divisible space which underlies them and considering only their mobility [………]; you will thus obtain a vision of matter” (Matter and Memory: 276).

Still, Bergson insists, there are blockages to obtaining this: primarily, that we need to get things done. But he also charges mechanistic thinking (and “modernist epistemology” wielded with Occams’s razors, to shave experience to the skin, or to bifurcate nature from culture, etc.) with this crime. Mechanistic thinking, for Bergson, does many things but it primarily spatialises experience. Imagine billiard balls hitting one another in an abstract space: is this what “matter” is? Is this how “nature” “functions”? Bergson often uses this example: imagine moving your hand from A to B. We can spatialise it as a movement from A→B. We can trace the movement whereby the line represents a movement. We can then divide it up into a series of locations/positions. We can even divide it further, infinitely. Read: Zeno’s paradoxes (another favourite). Is this infinite division of the line into points, which we can measure in extensive magnitudes, what movement is? ——- > ? Does the “arrow”, a direction/vector, help? We could then recompose it from these points: → . For him, this is still not what movement is: “we discover here, at the outset, the illusion which accompanies and masks the perception of real movement [………]. You substitute the path for the journey, and because the journey is subtended by the path you think that the two coincide. But how should a progress coincide with a thing, a movement with an immobility?” (MM 248). “A trajectory,” he continues, “can be infinitely divisible into extended points; but movement is an undivided fact, or a series of undivided facts” (MM 251). Movement is not spatial translation, from point A to point B. Movement is a transformation. It is not a displacement from a point on a trajectory. It is an event. (Clearly, ANT’s notions of translation/mediation take root here “on the wind”.)

Okay. He argues that by measuring objects in space we tend to “localise” objects in space. They are projected into a homogenous, geometrical spatial framework. They are abstracted out of the real movement of matter. It should be noted that he says repeatedly that this is in the vocation of science, in pragmatic pursuits, but that the philosopher can do different! Nevertheless, this, for Bergson, constitutes a “solidification of the real” (MM 280). Movement slows down infinitely: “homogenous space and homogenous time are then neither properties of things nor essential conditions of our faculty of knowing them: they express, in an abstract form, the double work of solidification and of division which we effect on the moving continuity of the real in order to obtain there a fulcrum for our action, in order to fix within it starting-points for our operation, in short, to introduce into it real changes. They are the diagrammatic design of our eventual action upon matter” (MM 280). Localisations and solid objects are cut-outs, immobilities seized through perception and for action. William James called them “substitutions”; they diagrammatically inscribe themselves into the real to help us plan our doings. But, if we “misplace” this abstraction as something concrete (Whitehead 1929), as what reality is, then we make a fundamental mistake.

Alfred North Whitehead has called this the “principle of simple location” (or the fallacy of misplaced concreteness): an abstraction that insists we can place something into a discrete bit of space and time, cut off from its relations to other places and times. He writes, in Science and the Modern World, “To say that a bit of matter has simple location means that, in expressing its spatio-temporal relations, it is adequate to state that it is where it is, in a definite finite region of space, and throughout a definite finite duration of time, apart from any essential reference of the relations of that bit of matter to other regions of space and to other durations of time [………]. I shall argue that among the primary elements of nature as apprehended in our immediate experience, there is no element whatever which possesses this character of simple location” (1929: 74). Whitehead and Bergson agree.[1] As noted above, this is an issue, sometimes. As Didier Debaise notes, in Nature as Event: the Lure of the Possible (2017), that when this is confused, when materialism is based on simple location, it is a mere formalism, devoid of matter. This is what Bergson is saying too. When you confuse the spatialisation of reality with reality, and then develop a theory of matter based on that, you get a materialism without matter! We can say, with Bruno Latour (2007), that Bergson (and Whitehead) are asking for their materialism back. It should also be noted, with Debaise and Latour and Whitehead and James (and who else?) that this also bifurcates the world: when matter is associated with primary qualities, localisable in space and time, as brute matter, as spatio-temporal particles that bounce off one another, where cause and effect can be mechanically mapped, then everything else becomes phenomenal, subjective, cultural, accidental (secondary)………not part of what exists in “nature”.

In his essay on Bergson – to come back to waves – de Broglie writes, “always guided by Zeno of Elea, Bergson seems to have foreseen this [the principle of non-localisation in quantum physics – you can either measure an elementary physical entity in geometrical space, but this deprives it of its mobility, or you can measure the dynamism of an entity through its quantity of motion/energy, but then you cannot find it in a location in space] [and], he could have said, using the language of quantum theories, ‘if one attempts to localize the moving object, through a measurement or an observation, at a point of space, one will obtain only a position and the state of motion will entirely escape” (53). So: quantum theories and Bergson show that any attempt at localisation in homogenous space deprives whatever is being localised its movement; and that wave theories can help us to think about movement and matter (and matter is movement, albeit at different rates of speed) without subtending it with a concept of simple location (or on solid ground).

In Matter and Memory, Bergson refers to Clerk Maxwell and Faraday because their theories of matter, or rather, insofar as they think about matter via movement, can get us out of the logic of solidification – and to think “on the wind” as it were. This is Bergson: “But the materiality of the atom dissolves more and more under the eyes of the physicist. We have no reason, for instance, for representing the atom to ourselves as a solid, rather than as liquid or gaseous, nor for picturing the reciprocal action of atoms by shocks rather than in any other way. Why do we think of a solid atom and why of shocks? But very simple experiments show that there is never true contact between two neighbouring bodies [here he refers to Clerk Maxwell]; and besides, solidity is far from being an absolutely defined state of matter [again, Clerk Maxwell]” (MM 262-3). Solids are not absolute. There is something more to matter than its solidity. The problem with the atom is that it is delineated through an outline that circumscribes its limits, that sets it apart, that, like a fence, prevents it from leaking out; an outline corrals what is diffuse, a form to contain content. Again, Bergson: “The preservation of life no doubt requires that we should distinguish, in our daily experience, between passive things and actions effected by these things in space. As it is useful to us to fix the seat of the thing at a precise place where we might touch it, its palpable outlines becomes for us its real limit, and we then see in its action a something, I know not what, which being altogether different, can part company with it. [2] But since a theory of matter is an attempt to find the reality hidden beneath these customary images, which are entirely relative to our needs, from these images it must first of all set itself free………” (264).

Set free, we no longer have individual objects interacting with other individual objects in a homogenous space. Bergson turns to Faraday: “We may still speak of atoms; the atom may even retain its individuality for our mind which isolates it; but the solidity and the inertia of the atom dissolve into movements or into lines of force whose reciprocal solidarity brings back to us universal continuity [………]. [Faraday] means by this [centre of force] that the individuality of the atom consists in the mathematical point at which cross, radiating throughout space, the indefinite lines of force which really constitute it: thus each atom occupies the whole space to which gravitation extends and all atoms are interpenetrating” (MM 265). And so, another principle of non-localisation: if we begin to think of matter as movement, then there are no outlined objects in a homogenous space or medium because it suffuses the entirety of space around it. It is atmospheric: A force field. There are not individuals against a background, but superimposition, overlaps, merges. Not a Galilean world, partes extra partes, but a radiating force: the wind moving the leaves of a tree, the noise of traffic as energy pushing its way into your bedroom lying awake at night.

Instead of partes extra partes, Bergson writes that the images of vortices and lines of force (albeit only “convenient figures” for the physicists) “show us, pervading concrete extensity, modifications, perturbations and changes of tension or of energy, and nothing else” (201). Movements all the way down. Milic Capek, in his essay on Bergson and physics, writes “Confirming Bergson’s prophecy that change has no need of support, microphysics refuses to speak of vibrations of something, but speaks simply of “waves of probability’, that is, of pure events, of changes which do not imply things which change [………], events at the very foundation of being” (321).[3] Things, for Bergson, are just slackenings of movement, of vibrations slowing down, different rhythms.[4]

This in turn means that there is a somewhat mysterious vibrating micro-verse beyond our partial views, beyond our regimes of perception based on abstract bodily schemas: “to say this is to say that what we seize, in the act of perception, something which outruns perception itself, although the material universe is not essentially different or distinct from the representation we have of it [………]. Matter thus resolves into numberless vibrations, all linked together in uninterrupted continuity, all bound up with each other, and travelling in every direction, like shivers through an immense body” (MM: 275-6). He, Bergson, uses the example of the sensation of “red light”, a contraction of billions of vibrations (see p. 272) that we are only “dimly aware” of. That is, while we see “red”, we do not perceive the billions of vibrations, we simply contract, and we are not really perceptive of these contractions, this sensory experience; it is at the fringe, or beyond, how “humans” perceive. There is, in the words of William James, a “blooming, buzzing confusion” of the world in experience; our point of view is but a thin slice of clarity and distinctness of the obscure and confused world that murmurs beyond us, but of which we are part of. In Deleuze’s lecture on Leibniz, he speaks of Leibniz’s concept of “little perceptions” and discusses this through the metaphor of the wave: “you are near the sea and you listen to the waves. You listen to the sea and you hear the sound of a wave. And Leibniz says: you would not hear the wave if you did not have a minute unconscious perception of the sound of each drop of water that slides over and through another, and that makes up the object of minute perceptions. There is the roaring of all the drops of water, and you have your little zone of clarity, you clearly and distinctly grasp one partial result from this infinity of drops, from the infinity of roaring, and from it, you make your own little world, your own property”.[5] In the same way, Bergson speaks of these partial views of an infinite world of vibrations, that roar of the sea, the infinite roar of waves………

Back to the movements themselves! Bergson, the thinker of duration of flux of movement of continuity is in a way asking us to think “on the wind” through the wave, a metaphor, but also literally, of movement in itself. Movements do not lead to a solidification of the real, to simple locations, to homogenous space-times, and ask us to instead think of intensities and multiplicities, to turn the world into one of vibrations, of speeds and slownesses, where solid things are but the slowing down of movements, cut-outs from the clamour of the world.

One more Deleuze reference. In A Thousand Plateaus, with Guattari, they write of the medieval concept of “haecceity” (from Duns Scotus), a form of atmospheric or diffuse individuality. They write that we are nothing but haecceities:

“you are a longitude and a latitude, a set of speeds and slownesses between unformed particles [c.f “waves of probabilities”], a set of nonsubjectified affects. You have the individuality of a day, a season, a year, a life (regardless of its duration) – a climate, a wind, a fog, a swarm, a pack (regardless of its regularity). Or, at least, you can have it, you can reach it [………]. It should not be thought that a haecceity consists simply of a décor or backdrop that situates subjects, or of appendages that hold things and people to the ground. It is the entire assemblage in its individuated aggregate that is a haecceity; it is this assemblage that is defined by a longitude and a latitude, by speeds and affects, independently of forms and subjects, which belong to another plane [………]. Climate, wind, season, hour are not of another nature than the things, animals or people that populate them, follow them, sleep and awaken within them. This should be read without a pause: the animal-stalks-at-five-o’clock [………]. Five o’clock is this animal! This animal is this place!” (262-263).[6]

Longitude, latitude, haecceity: concepts, maybe, for characterising the individuality of the wave, events, movements. Not a translation in space, but a transformation of a “whole” – a way to grasp something happening………

“in water or on the wind”.

[1] It should be noted that Whitehead also has a chapter in Science and the Modern World where he discusses wave theory and quantum physics in relation to a theory of perception and of matter (see chapter “The Century of Genius”).

[2] This “effect”, this “action” which is “a something, I know not what” which “parts company” with the two things that interact with one another is, however, I think something to hold onto. This idea that there is a something, an action, that is somehow different from the interactions of matter is maybe what the Stoics refer to as an event, an Incorporeal (e.g., a knife cuts into butter – knife and butter, things, and cutting is an incorporeal body, an event, another “mode” of being that exists at the surface).

[3] The “air,” in this line of thinking, is not the medium through which waves travel (is not the air often a replacement for the ether, which is in turn a replacement for the isotropic, geometric space of Newtonian/mechanistic physics?). Perhaps it is better to think not of “media” but of events: matter-space-timings (as Barad would say), the matterings, the durations. Rather than laying a foundation for waves in the air through the air (as if clouds could hold anything anyway), there is something that happens, an immanent movement.

[4] Capek again: “thus the last traces of the Lucretian concept of nature disappears: the identity of particles and the continuity of their trajectories, which are only illegitimate extensions of macroscopic concepts into the world of atoms and photons [………]. Evidently what classical physics designated as a ‘particle’ is nothing less than an often temporary local disturbance of the chronotopic milieu; hence the close connection of the ‘corpuscule’ with its surrounding environment as well as its capacity to be dissolved completely into its environment” (321).

[5] See: http://deleuzelectures.blogspot.com/2007/02/on-leibniz.html.

[6] The hyphen, which has become so common, also comes from Bergson in Creative Evolution (the hyphen: a sign of the wave operating in a text): “Evolution implies a real persistence of the past in the present, a duration which is, as it were, a hyphen, a connecting link. In other words, to know a living being or natural system is to get at the very interval of duration………Continuity of change, preservation of the past in the present, real duration………unceasing creation………” (24).