This is a talk for the panel “Aerial Leakages” as part of the 2024 STSing conference in Dresden, Germany, March 19-21.

Decibel Hunting

In 1999, the municipal council of Paris held a discussion about their ongoing “lutte contre le bruit” (or struggle against noise) – the name given to France’s policies and programmes around noise issues. This was at a time when “noise” was increasingly being understood as public problem in Paris and France – in terms of environmental and public health as well as for urban governance. During the discussion at the city hall, the then mayor of Paris, Jean Tibéri had announced several projects to combat noise, signalling a turning point in how the city would deal with it. The most significant being the inauguration of a noise observatory (at the time, modelled after the traffic observatory; the more recent noise observatory is modelled after the air pollution observatory – also an indication of a change in how noise is understood) whose purpose would be to develop a “global image” of noise based on “objective” principles, to objectify the noise problem in order to be able to act upon it and evaluate these actions – an apparatus for tracking noise, or what another politician during the meeting had cheekily called (echoing a term used frequently in the media) “la chasse aux decibels,” or the hunt for decibels – a hunt that is for sound pressure levels in the air, but also for their troublesome noisemakers.

“The Decibel is a difficult game to Hunt” (Source: Les Echos)

Drawing from my fieldwork in Paris last spring and summer largely with the regional noise observatory called Bruitparif, in this talk I would like to just reflect on this idea of a hunt for decibels as a way to think about and contrast with listening to noise. More specifically, I am interested in the epistemological challenge of listening to noise, or, as in the case of the acousticians that I followed, what it means to listen to others’ noises, or to others listening to noise.

Hunter/Hunted

Briefly, the hunter, the noise observatory is a technoscientific organisation whose task is to hunt for decibels – even if they describe themselves as the “noise watchdogs”. They have a large-scale network of measurement stations across Paris alongside project-based, temporary stations; they do “sensibilisation” work with communities; produce reports, conduct studies, innovate technology, evaluate noise policies. Their aim, they told me, is to provide an “objectification” of the noise problem, ultimately, through decibels (as you can see on the noise map – one type of trap for sound).

To understand what it means to hunt for decibels, we should also probably have an idea of what a decibel is. The decibel historically comes from the realm of communication technology where scientists at Bell Laboratories tried to determine the signal-to-noise ratio needed to listen through telephones; in terms of sound, it measures the sound pressure levels in the air, or the change in air pressure as a sound wave passes through it. It measures the movements of the air.

An acoustician working for the city of Paris defined it in this wonderful way:

It’s the pressure. The acoustic intensity [is] a level of pressure […]. You can hear the pressure. It’s a level of the acoustic pressure of the air. We have the air, and it moves with the pressure. The more energy you have, the more it makes your hair move, and you can hear that.

The decibel is a way to measure the air as what moves your hair. The decibel is a way to measure the air as what moves your hair.

In other words, again, the decibel – with all of its complications – allows the acousticians to fix a trace of what does not leave traces, a way to ground the airborne, to slow down what flees to trap it. But, as we know, noise is not the same thing as sound. Noise is traditionally and conventionally understood as annoying or unwanted sound. And as you can see in this diagram from the 1960s, there is a whole process for sound to become noise as it is understood by acousticians, whether psycho- or socio-oriented.

In the next section, I will quickly recount a noise measurement that I attended with an acoustician, Céline, as she is hunting for decibels. But I am also interested in thinking about whether this measurement could be an instance of what Timothy Choy (and others) have called “apparatuses of atmospheric attunement,” as ways of attending to elusive, fleeting things. In particular, I am interested in whether Céline’s method of listening can capture the leakiness of noise (as what is not contained in the decibel). Choy, for instance, develops a concept of “suspension” to describe a mode of attunement to the smells of mushrooms, and there is short sentence on page 59 that I think is helpful. He writes, “Suspension implies not a vessel or a container, but a current” (2018: 59). You attend to elusive things in their current (not by capturing them in a jar or maybe a decibel), but in the ways they flow, their leaks.

I am interested in what this “current” could be in a measurement of noise, and whether Céline’s listening attends to it.

Listening and Measuring

I meet Céline and a city official from the local mairie outside of the home of someone who has made a noise complaint. He meets us at the gate to his house, and as we enter his yard, he asks us to pause and listen. “Do you hear that?” Céline nods. They both point toward the roof of a nearby building where the source of the annoyance hisses. It is ventilation equipment. I too can sort of hear the hisss but not well.

Sonometre set-up (Source: Author)

We then go upstairs to his bedroom where the measurement will happen. The first thing they do is deliberate where the measurement device should stand. The complainant opts for the window that does not directly face the “source” of the noise as that is where he said that he received the highest sound level reading through his own device. Céline then sets up her measurement device and stands silently, for a few minutes, listening out the window.

Here is her “ear-view”:

Can you See the Noise? (Source: Author)

As we leave to go downstairs, the complainant compares his own device with Céline’s. With a wink, he says to me: just making sure.

Once downstairs, we sit and drink coffee while the measurement takes place upstairs. The measurement is for what is called “bruit de voisinage” or neighbourhood noise – a noise that is not environmental noise or industrial noise. There are different regulations, methodologies, and limits. Different understandings of noise and configurations to make it appear.

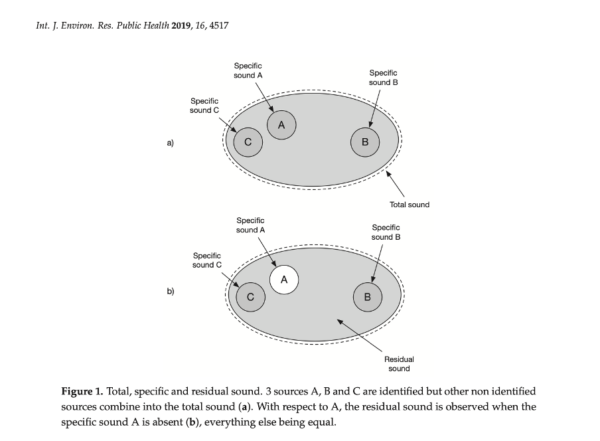

Sound Emergence (Source: Fredianelli, Lercher, Licitra 20222)

They use the methodology for “sound emergence” (a differential noise indicator): they want to measure how much the source adds to the total sound environment, to the background noise. To do so, they do a 30 minute measurement with the source “on” and with it “off” – there is an issue only if the source adds 5 dB(A) to the background. One reason they do this is that it is an attempt to get as close as possible – through the physicality of sound as a pressure in the air – to the “annoyance” of the complainant, to what he perceives. In other words, through a purely acoustic approach, that is, through the physicality of sound, the decibels, it is an attempt to listen as others listen, that is, to capture their noise.

Checking for Decibels Nearby (Source: Author)

While we wait for the measurement device to do its job, the complainant is constantly sticking his own device out various windows. He is anxious for those 5 dB(A)s to appear. During the second measurement (with the source turned “off”), for instance, he asks us if we can still hear something. He listens out the door to his garden. Yes, he says, there are still sounds coming from the neighbour’s property, interfering in the measurement. He asks the city official to call to see if they could turn them off (that is, to ask the construction workers to stop). He does and they do. It gets noticeably quieter. Everything is “turned off”. But there is a cruelty to noise: it always returns. We now begin to hear more clearly the airplanes overhead, the sounds of traffic, neighbours vacuuming, distant voices, construction noises further away. The complainant is frustrated and the official jokes that he does not have the power to turn everything off.

The complainant then turns to me and says that he has a good ear, too good; it comes with consequences.

When the 30 minutes is up, Céline collects her equipment, and we leave.

Reporting on the Measurement (Source: Author)

The next day in the offices of the observatory, Céline is cleaning the data. She tells me that unfortunately the level added was not more than 5 dB(A), and that this man will have to find other means to turn off that noise – and seems a little upset by that.

Later in the day, I ask Céline what she was listening for out the window. She told me that first – perhaps a little strangely – “it’s always important to listen with your ears” (that is, to not just rely on the decibels), and that, on the other hand, listening for her involves listening to the backstories of the complainants, to try to understand the context, their histories – how the noise emerges, but not just as a sound. As, in this case, the level of the sound, the decibel reading, may not actually be that high, and yet there is still annoyance, still noise.

It’s important, she tells me, to listen to how that annoyance emerges: for instance, you begin to notice something, you cannot stop paying attention to it, and it “amplifies,” as she says, in your experience. An “amplification” that may not be legible in the decibel or in the air.

Céline’s definition of listening points quite well to where I think acousticians hunting for decibels often “hesitate”: the challenge of listening to others listening to noise. Or, somewhat differently, what Marina Peterson (2021) has called the “dynamic friction” between the inscriptions of noise and its experience – dynamic because it never settles; it is perhaps where the “hunt” happens.

Listening to Noise, a moving target

I just want to quickly conclude with a reflection on this hesitation that the acousticians have when they listen to noise by returning to the idea from Choy. That this is a form of attuning to the leakiness of noise, of trying to “capture” it, not in containers, but as a current, as it leaks. Listening is could thus be understood as paying attention or attending to this dynamic friction or hesitation, between the decibels and the ear, between the configuration of the measurement and the experience of the complainant, etc. But also, to the indefinite nature of noise: you cannot turn off the sound environment totally: there is always another. But indefinite also in each attempt to “capture” it: that is, in decibels, through the microphone, in a methodology, specific indicators or noise maps, the “noise” is always displaced.

My hypothesis is such: that listening as a form of attunement to noise is not just multimodal (using different types of sensors) or cross-modal but about attending to the leaks between them, of following it as a moving target and to grasp it in and as a current.

This also runs in parallel with Roland Barthe’s short essay on listening (written with his then secret partner Roland Havas, a psychologist):

“what is listened to here and there […] is not the advent of a signified, object of recognition, or of a deciphering, but the very dispersion, the shimmering of signifiers, ceaselessly restored to a listening which ceaselessly produces new ones from them without ever arresting their meaning” (1991: 259).

In other words, the hunt for decibels is maybe better described as a never-ending chase for noise.

References

Choy, Timothy. “Tending to Suspension: Abstraction and Apparatuses of Atmospheric Attunement in Matsutake Worlds”. Social Analysis 62 no. 4 (2018): 54-77.

Peterson, Marina. Atmospheric Noise: The Indefinite Urbanism of Los Angeles. Durham: Duke University Press, 2021.

Barthes, Roland. “Listening” in The Responsibility of Forms. California: University of California Press, 1991. 245-260.