Jorge Martín Sainz de los Terreros is an architect, urban designer and researcher. During the last five years, he has worked as a public official at the Council of Madrid, and currently he develops his postdoctoral research at the Institute for European Ethnology at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. His research mainly engages with questions about issue publics and participation. His doctoral thesis explored how temporary urban spaces could become eventual publics and how that related with everyday practices of care. Most recently, he is focussing on heat and climate change controversies in urban environment and cities. He is a member of the ERC project WAVEMATTERS, and studies the conceptualisation, problematisation and operationalisation of heat in public policies, plans and projects in the city of Madrid.

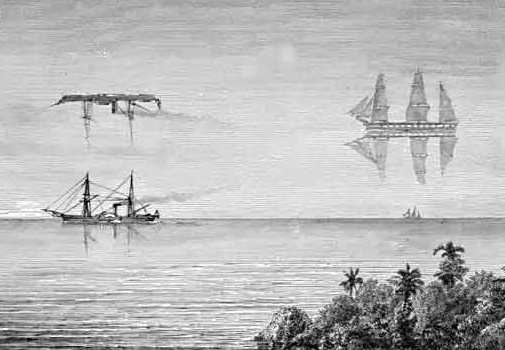

1872_Frank R. Stockton – Round-about Rambles in Lands of Fact and Fancy – Scribner, Armstrong & Company

In physics, a mirage is an image that can be seen under specific atmospheric conditions; an optical illusion caused by the refraction and eventual total reflection of light rays through layers of air that differ in density as the result of an unequal distribution of temperature. It usually happens in the volumetric space just above hot surfaces that have been exposed to the sun—like sand in the desert or asphalt—and produces the effect of making one see things that are not there; for example, reflections of faraway objects or the feeling of seeing the surface of water that mirrors the sky above it. For a mirage to emerge, three different conditions are needed: first, something—i.e. a surface or an object—requires some heat (via radiation or other means); secondly, the layers of air above it change in density—some thickening, others lightening—and that produces a flickering effect in faraway visions due to the reverberation of light rays that pass through those varied layers of air; and thirdly, if the specific density of air allows and the right conditions coalesce, an image of a reflection appears in the distance—often near the horizon. There is a mirage. A mirage is thus not an isolated vision imagined in your head, but is a speculative setting where actual and virtual visions merge into an image due to the thickening of air that has been heated.

The concept of mirage is commonly used as an indicative of visions, images or ideas detached from reality; those that make no sense to pursue further due to their lack of grounding in the “real” world. Particularly in the Sciences, to question “mirage or reality?” is a way to clarify—or sometimes even judge—the positionality of the author, and to argue for “scientific” or “technical” facts against speculation. Mirages are often argued to be differentiated from reality—i.e. that they are not real or factual—and thus, dismissed: “Only facts are real; and only knowledge based on facts is true! That is with what scientists should work with! Don’t be tricked by mirages!”.

However, mirages are not exactly “unreal” in the sense that they are non-existing. They have a different mode of existence. This can be traced etymologically. For instance, in Spanish, mirages are espejismos, which are etymologically linked to the word espejo [mirror], from the Latin speculum. Also related, to speculate comes from the Latin speculor which means to observe. The word mirage, on the other hand, comes from mirari, to wonder or admire, and is linked both to mirror and miracle. Mirages are indeed immaterial mirrors that afford observing things differently—e.g. upside down or stretched. The images and visions that are seen in them are real, for they are, to follow Deleuze, “actual and virtual” at the same time (Deleuze and Parnet 2007). On the one hand, mirages are actual, because the processes through which they emerge are material and eventual; they can be materially sensed. The images that are experienced are actual and can be shared in a common experience—e.g. they can be photographed. Mirages, on the other hand, are also virtual for they trigger thoughts, actions, and knowledge that spark possible links between the optical images seen with memories and imagination, or other possibilities. Hence, the result of those links are not only products of our imagination, but they are eventual entanglements of real-virtual images in a continuous process of actualization.

But why engage with the concept of mirage? What does it offer for the development of a wavy social theory? Well, it allows understanding the conditions under which certain speculative thinking processes produce specific wave-like reflections. This speculation around and through mirages is not necessarily concerned with the meaning or the usage of mirages in literature, but rather with the conditions and situations that ignite them into being, what makes mirages emerge. My point being that it is not only worth attending to mirages because they allow us to theorise practice around imagination or to ethnographically understand certain specific encounters, but also because they might help understand the situations within which images, ideas or visions that are in the process to be defined are enhanced, discussed, developed or imagined. In that sense, the idea of mirage could be used to engage the process in which visions that are at a distance—faraway, not yet clear, in the process of being materialised, eventualised, actualised or thought—can be seen, imagined or visualised due to the effect of some sort of heated situation, whether actual or metaphorical. In those situations, heat—or sets of relations, debates and controversies that have become heated—might allow for certain images to flicker; images that are there, that can be shared with others, yet might not be a second after, or might not link to similar common thoughts, but conflicting views, uncertain views.

Importantly, mirroring its physical sense, three different concatenated phases need to happen for a mirage to emerge (and remain mirage-like). First, an issue has to be heated, for, in a mirage, it is heat that sparks mirages into being – to paraphrase “issues spark publics into being” (Marres 2005). A heated issue is one that raises questions and concerns that direct—and sometimes diverge—discussions and debates, and change the density of knowledge around it, so that an unexpected flickering of thoughts could align and things that previously could not be seen appear at a distance, or come together in ways that otherwise, if not as mirage, could not be related. Hence, conceptually, a mirage is different from Donna Haraway’s concept of “figure”, for even if it can also be a “creature of imagined possibility and [..] fierce and ordinary reality” (2008, 4)—i.e. real and virtual—it also sustains an atmospheric unreality, an ungraspable flickering density, like fire objects (Law and Singleton 2005). As a result of the alignment of flickering thoughts, a vision linked with a new density of knowledge sparked by a heated situation might be eventually materialised. Mirages, in that sense, are eventual—that is, both “provisional and actual”(Martín Sainz de los Terreros 2021) — held in suspension, and might disappear as quickly as they have appeared; so you better note them down before they go.

Still, mirages are not only built up from what you see, but also from the particular—cultural, historical, geographical (Wachsmuth and Angelo 2018)—circumstances and contexts through which they become visible. Visions are thus reflected images linked to previously sedimented knowledge. Mirages reproduce what is known but organise it differently. Hence, the emergence of certain types of mirages is limited and shaped by knowledge, by what is known and the relationships that knowledge entails. They are entanglements of possible imagined (but also materially real) enactments of possible configurations that emerge from what Law would call “hinterlands” (2004)—that is, not only individual but also social and common knowledge and experience.

A mirage, then, could be understood as a device: a “patterned teleological arrangement” (Law and Ruppert 2013) that can be purposefully used. One could set up the conditions for a mirage to emerge—this “patterned arrangement”—and wait for it as in an experimental exploration. The image that might appear, however, is not necessarily controlled; it depends on the type of heat and the density of air needed—that is, the conditions in which the heated issue is discussed, the type of participants of the experiment, the kind of background those participants carry with them, and so on and so forth. Alternatively, heat might also emerge from an unexpected place or time, where an issue may develop in surprising directions. The heat that sparks visions into being then could be purposeful (premeditated) or surprising (emerging); likewise, the density of knowledge that it triggers. In that sense, the experiment might, even if planned, also, like a mirage, trick the expert. Hence, a mirage could be understood as a device, but not only like a machine that mediates and specifically does what it is meant to do, but also in a more ambiguous sense: as a vision that can trick, a deceiving, devising and even deceptive tool. Its purposefulness, in effect, is linked also to the possible involuntariness of its results, to the surprising experience of encountering something new. To learn something is to be open to new knowledge. As Stengers (2018) would claim, a good experiment is one that surprises. Speculations nevertheless do not come from nothing. To speculate is to make the link between that surprising experience of emergence and the imagined features that are brought from your own memory and background: it is to squint into the wavering image of the mirage, stretching, as it does, from the real to the possible, as a virtual not yet actualised—there, but not quite, as a flicker of existence.

As a wavy social concept, a mirage does not refer to “unreality”, but to the open processual possibilities of the emergence of thought, whether teleological, logical and purposeful or surprising, astonishing and unruly, and to the capacity to link those emergent thoughts with previous memories and imaginaries so that new knowledge and possible alternative futures can be eventually actualised.

References

Deleuze, Gilles, and Claire Parnet. 2007. Dialogues II. Rev. ed. European Perspectives. Columbia University Press.

Haraway, Donna J. 2008. When Species Meet. University of Minnesota Press.

Law, John. 2004. After Method : Mess in Social Science Research. Routledge.

Law, John, and Evelyn Ruppert. 2013. ‘The Social Life of Methods: Devices’. Journal of Cultural Economy 6 (3): 3. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2013.812042.

Law, John, and Vicky Singleton. 2005. ‘Object Lessons’. Organization 12 (3): 3.

Marres, Noortje. 2005. ‘Issues Spark a Public into Being, A Key but Often Forgotten Point of the Lippmann-Dewey Debate’. In Making Things Public: Atmospheres of Democracy, edited by Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel. (Mass.) : MIT press.

Martín Sainz de los Terreros, Jorge. 2021. ‘Eventual Publics: An Enquiry on Socio-Material Participation in El Campo de Cebada, Madrid’. In Doctoral Thesis, UCL (University College London). UCL (University College London). Ph.D., UCL (University College London). https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10121911/.

Stengers, Isabelle. 2018. Another Science Is Possible: A Manifesto for Slow Science. Polity press.

Wachsmuth, David, and Hillary Angelo. 2018. ‘Green and Gray: New Ideologies of Nature in Urban Sustainability Policy’. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 108 (4): 1038–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2017.1417819.