Brett is a postdoc at the Institute for European Ethnology at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin as a member of the ERC project “Urban Vibrations: How physical waves come to matter in contemporary urbanism”. As part of this project, he studies how noise is shaped through and undoes infrastructure and technoscientific forms of knowing in Paris and how 5G-associated infrastructure, antennas and the spectrum, reshape the city and how they are contested by social groups in the UK. He has recently published a monograph called Variations of a Building (2023) that draws from his PhD dissertation completed at the University of Manchester. His research happens at the intersection of design, infrastructure and technoscience, interested in ambiguous objects, imprecise knowledges, and worlds incomplete.

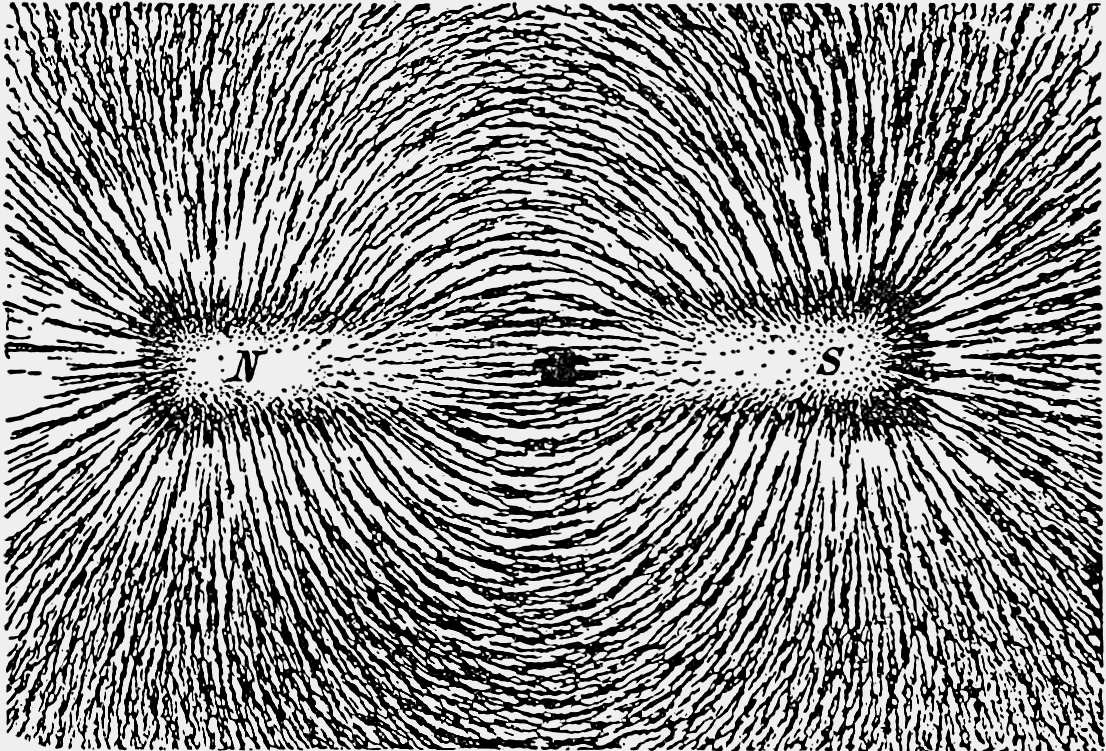

Newton Henry Black – Black, Newton Henry; Davis, Harvey N. (1913) “fig. 200” in Practical Physics, United States: The MacMillan Co., pp. 242

There is a force of things: a vibrancy or intensity, an effectivity, like radiation, a field that envelopes, captures, emanates, irradiates, connecting things across distance. A force that happens due to the way in which things are brought together, or a force emitted from when they break apart. Discourse and words can have a force — illocutionary, for instance — on the way in which things are arranged. Spaces too are said to have a force as an arrangement that shapes a disposition, that constitutes possibilities, or limits them. There are the physical forces, like gravity and electromagnetism, or frictional forces, viscous and material, or molecular and nuclear forces. There are the forces of attraction and repellant forces. A mechanical push and pull, a tension, an electric static. Military forces, police forces, forces of production, and labour forces. The will has a force — if you will it — and the State has its legitimate use. There are, of course, the forces of nature, of law and love. There are quantities of force, and units and metrics to measure it. And yet forces are not quite things, but actions, movements, and intensities. They happen without media and form. Formless, force is, in a way, but not only, a dynamism in and of the world, that passes through the world, a passage of the world. Force comes from within, above, and beyond, or below. Perhaps each thing, composed and formed, possesses force. But force, to repeat, is formless. It is what is “inherent in the projectum” (Jammer 1957: 68), the movement of the mobile, the “seat of the mobile”, the dynamis, vis viva. There is the force of the wind, sound, and light (how it moves and produces movement); the force of a situation that hangs precariously there, of an atmosphere, threatening, perhaps, or joyful, the force of an encounter, an occupation, the force of the moon on the tides, of an electric current along a wire, of a scent, an image, bombs, of the way a hammer smashes down, or of the noise that persists forcefully as traffic sits idle, and then not. It is of a tension, a static stasis — stilled, yet not a cessation, but an equilibrium of forces, a field silently moving. There are relations of force that make visible and outline possibilities, that make some decisions available and others not, that make some existences legible and others not. Force, perhaps like tone or atmosphere or affect, does not refer to subjects and objects, but is autonomous, has another logic of being, and requires another way of seeing, another register of sense, metric, or way to capture it.

While “basic” and foundational in physics, force, as Max Jammer writes in his history of the concept, is maddeningly elastic, and elusive, which is nevertheless the source, perhaps, of its utility for imagining — or knowing — what is invisible, imperceptible, amorphous, barely there, and yet, forceful. Jammer’s history is as much about force as it is about its metaphorics — or metamorphics — and the challenge of clearly and distinctly figuring it out into a logic, of separating it from similar concepts: e.g., cause, potentia, vitality, dynamism, intensity, tendency, conatus, strain, push and pull, motion, a change in motion, momentum. Force has, for example, taken the shape of angels for Newton acting “across distance” (see Latour 2014), and in his article on how to make ideas clear, C.S. Peirce relied upon a parallelogram to clarify its clarity (1955: 33-36). Thus force – while useful – relies upon other forms to render it available and legible — as in angels, parallelograms, but also in lines.

In the 1830s, Michael Faraday troubled by the way in which electromagnetic induction — how electric currents induce magnetic fields — had interacted with the space or medium it passed through, along wire and wirelessly, began to question what that empty space could be. How did something happen there in between solid entities or atoms? Suggested to him by his sketches of iron filings scattering into patterns and arrangements in curved lines around magnets, Faraday described these invisible relations as “lines of force”, or elsewhere as vibration-rays. Maxwell would later call them “lines of induction” or “tubes”. It is from this idea that Faraday would also speculate about another theory of matter beyond atomism— as John Tyndall, the enthusiastic Faraday commentator and physicist, notes: Faraday abolishes the atomistic theory, “tossing it horn from horn” (1868: 151)—with its emphasis on solid impenetrable atom-like particles situated within an empty space. Instead, Faraday, based on his sketches, would argue that there are fields composed of lines of force with concentrations and divergences, of curvilinear lines, that would sometimes gather and circle around into elastic (Boscovichean) “centres of force” full of tension, or shoot off into lines of flight elsewhere. As he writes, “to my mind, therefore, the […] nucleus [of an atom] vanishes, and the substance consists of the powers [i.e. “force”] […] all our perception and knowledge of the atom, and even our fancy, is limited to the ideas of its powers” (1846) i.e., its force, its effectivity, its capacity, of what it can do. For Faraday, then, it would be easier to describe what happens through verbs than nouns, through capacities, powers, or forces (of relation) rather than atom-like entities. Atoms are thus “highly elastic” rather than “hard and unalterable in form” (1846); they are not unlike, in an image he develops, “the compression of a bladder full of air.” One should then refer to things, as tense knots of force, through their “disposition and [the] relative intensity of the forces” (1844: 137) that compose it. They are this “relative intensity” of force. Rather than an “impenetrability of atoms”, Faraday described their mutual penetrability as a kind of entanglement, a relational ontology. “The particle indeed,” Faraday writes, “is supposed to exist only by these forces, and where they are it is” (Faraday 1846: 347). Each thing exists through its relations of force. Faraday:

“the smallest atom of matter on the earth acts directly on the smallest atom of matter in the sun […] further atoms, which, to our knowledge, are at least nineteen times that distance [between earth and sun], and indeed in cometary masses, far more, are in a similar way tied together by the lines of force extended from and belonging to each” (Faraday 1846: 347).

For Faraday, lines or relations of force, in a quasi-Nietzschean way, constitute reality by “tying” things together. Through a Faraday-vision, subjects and objects, matter and atoms, are the products of lines of force that swirl into centres of force, that cohere in intensive forms, or densities and convergences. There are only the lines of force acting upon other lines of force. It is perhaps with Faraday and through his experiments that there is a new form of perception through microphysics: to see matter as force, solidities as tenuous densifications or temporary consolidations of force, and reality as traceable through lines of force in processes of formation, but also in variation, off-balance.

This logic of force has travelled into different theories in the 20th century. Perhaps most notably in the thought of Michel Foucault, who, via Nietzsche, in his famous analytic of power that he called a “micro-physics” (and later through his concept of “dispositifs”) studied power relations as relations of force. Force was used by Foucault as a means to shift the frame of reference from a “macro” level of politics (consisting of States, Ideologies, Sovereigns, etc.) down to what happens in practice at an everyday level. And, as Gilles Deleuze notes in a lecture on Foucault, that if “microphysics” is taken seriously, “we will find there the great microphysical unit: wave-corpuscle” [1]; waves and corpuscles thus become the units through which power is measured in molecular agitations and relations of force, rather than in the “macro” or large-scale phenomena associated with a classical physics of power. Power operates or functions through the very small (subatomic) and thus happens immanently to the social field that it constitutes, through practices, devices, utterances, discourses, technologies, buildings, people, documents, inventions, which act as so many relays; on the other hand, it propagates as line of forces in actions and activities, as exercises of power. Foucault’s anti-atomism of power, his microphysical analytic, maps power through fields of force, through which bodies and objects are disciplined, and subjectivities are produced. As he writes in, The Will to Knowledge almost in the same language as Faraday, power “must be understood in the first instance as the multiplicity of force relations immanent in the sphere in which they operate and which constitute their organization [….]. [Power] is the moving substrate of force relations which, by virtue of their inequality, constantly engender states of power, but the latter are always local and unstable” (1978: 92; emphasis mine). In the first instance, power is not possessed by subjects or relates to preexisting objects, but happens in “dispositions, manoeuvres, tactics, techniques, functionings; that one should decipher it [power] in a network of relations, constantly in tension, in activity” (1977: 26). As he writes later, in relation to his study of government, power is a “mode of action upon the action of others” (1982: 789). Relations of force — power — are actions upon other (possible) actions — other relations of force. This is a world, like Faraday’s, that is first of force. Forces incite, combine, relay, or delay other forces, which can, as he writes, eventually, “form a general line of force” (Foucault 1978: 94) that constitutes convergences, alignments, and homogenisations — forms of knowledge, subjects, and objects.

Later, Foucault turns to the study of what he called “dispositifs”: systems of relations within a heterogeneous ensemble through which power and knowledge are intertwined. Here Foucault explains:

I said that the apparatus is essentially of a strategic nature, which means assuming that it is a matter of a certain manipulation of relations of forces, either developing them in a particular direction, blocking them, stabilising them, utilising them, etc. The apparatus is thus always inscribed in a play of power, but it is also always linked to certain coordinates of knowledge which issue from it but, to an equal degree, condition it […] strategies of relations of force supporting, and supported by, types of knowledge (1980: 196).

Force remains the dimension through which to capture power. In his article “What is a Dispositif?” Deleuze describes this dimension of power, seemingly in reference to Faraday, as “lines of force”. Dispositifs, writes Deleuze, are “multilinear”, “composed of lines of different natures” (2007: 338), “lines of visibility, utterance, lines of force, lines of subjectivation, lines of cracking, breaking and ruptures that all intertwine and mix together” (2007: 340). Lines of force operate by linking together lines of visibility and utterance as forms of knowledge. Like the iron filings around Faraday’s magnets, a dispositif — for Deleuze — is a map of a social field, of sedimented lines and solidifications or formations, but also of mutations, fractures, cracks and lines of force.

In Foucault’s microphysics, situations, plots, and scenarios become sets of relation held in tension, a socio-electric field. The way an atmosphere can feel tense, force one to behave differently, or how a gesture communicates power, the way in which everyday life is held together immanently and intensively, but also unsteadily, as a “moving substrate” of force. Dispositifs, Deleuze notes, do not map homogeneous, static or stable fields, but instead “follow directions, trace processes that are always out of balance, subject to changes in direction, bifurcating and forked, and subjected to derivations (Deleuze 2007: 338). Or, as Foucault writes,“relations of power-knowledge are not static forms of distribution, they are ‘matrices of transformations’” (1978: 99). There is a potentiality charged in each situation. New forms of knowledge can be sketched out in the formless — “invisible and unspeakable” (Deleuze 2007: 338) — lines of force in order to give shape to new forms of visibility or new forms of utterance. As much as a dispositif is the “archive” of forces sedimented into historical forms of knowledge, conditioning and maintaining the present, they are also sketches of forces of becoming, of what is to come.

References

Deleuze, Gilles. 2007. “What is a Dispositif?” in Two Regimes of Madness, revised edition: Texts and Interviews, 1975-1995. USA: Semiotext(e): 338-348.

Faraday, Michael. 1846. “LIV. Thoughts on Ray Vibrations”. Philosophical Magazine. 28. no. 188: 345-350.

Faraday, Michael. 1844. “A Speculation Touching Electrical Conduction and the Nature of Matter”. The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 24. 157: 136-144.

Foucault, Michel. 1982. “The Subject and Power”. Critical Inquiry 8 : 777-795.

Foucault, Michel. 1978. The History of Sexuality. Volume 1: An Introduction. Translated by Robert Hurley. Pantheon Books, New York.

Foucault, Michel. 1977. Discipline and Punish. The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan. Vintage Books, New York.

Foucault, Michel. 1980. “The Confessions of the Flesh” in Power/Knowledge. Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-1977. Edited by Colin Gordon. Translated by Colin Gordon, Leo Marshall, John Mepham, Kate Soper. Pantheon Books, New York. 194-227.

Jammer, Max. 1957. Concepts of Force. A Study in the Foundations of Dynamics. New York: Harper Torchbook.

Latour, Bruno. 2014. “Agency in the Time of the Anthropocene.” New Literary History 45.1: 1-18.

Peirce, C.S. 1955. “How to Make Our Ideas Clear” in Philosophical Writings of Peirce. Edited by Justus Buchler. New York, Dover Publications. 23-41.

Tyndall, John. 1868. Faraday as A Discoverer. London, Longmans, Green, and Co.